Worthy of recognition

11/2/98

|

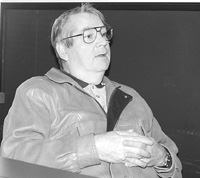

| Cyril Myrick |

|

|

By BOB BENSON

The Telegram

Cyril Myrick, whose family’s roots at Cape Race go back more than a century, has

added his voice to those who want the area southeast of the lighthouse to Chance Cove

declared a national historic park.

“It’s a historic area that needs full recognition,’’ Myrick said.

The Cape Race lighthouse has already received national historic site designation.

Retired Marine Atlantic master mariner Capt. Joe Prim, who is spearheading the campaign

for national recognition, said the area is of significant historic value because of its

connection with the sea, and the many shipwrecks which occurred along the coastline.

The St. John’s Golden K Kiwanis Club has already approached the provincial

government to declare Clam Cove, near Chance Cove provincial park, a protected site. It

contains the remains of more than 100 passengers who drowned in the wreck of the SS

Anglo-Saxon which ran ashore at South Head on April 27, 1863.

The Myricks have been lightkeepers since 1874.

Myrick himself also has a close association with marine history. He was the radio

operator on duty at Cape Race when Swedish and Italian liners collided off Martha’s

Vineyard, Mass. in 1957 and relayed and sent messages to the SS France during rescue

operations.

He was also the last operator at the federal Transport department’s marine radio

station in St. John’s to have contact with the offshore drill rig Ocean Ranger on the

night of Feb. 14, 1982, before the tragic loss of 84 men in the early hours of Feb. 15.

“My great grandfather, Paddy Myrick, was lighthouse keeper at Cape Race,”

Myrick recalled.

“One day the old fellow was repairing the roof on one of the houses when a rung

broke on a ladder and fell off and broke his neck. My grandfather, John, born about 1878,

also was a lightkeeper and he retired in 1928. My father, who was known as Big Paddy, was

also lightkeeper for several years until he retired in 1957.”

Myrick, 65, grew up and was educated at Cape Race and returned there to work as a radio

operator from 1954 to 1958.

The area was a delight for a young boy like Myrick.

“Growing up there was lovely,” he said. “I wouldn’t change it for

the world. There were wide open spaces, hunting, rock climbing, fishing out in boats. I

wouldn’t trade it and if I had it all over to grow up again, that’s where I

would do it.”

Myrick witnessed history in the making during the Second World War, when he attended

the Cape’s one-room school.

There were about 30 children in the school at the time. They belonged to families who

tended the light and the fog horn as well as the radio station. Indeed about 80 people

lived at Cape Race then.

The school teacher often let the kids out of school to see the big convoy formations

which passed by the Cape on their way to England with war goods and food for the

beleaguered country.

“Every second day the ocean seemed black with ships,” Myrick said.

“One day we were watching a convoy about 1,000 yards offshore when all hell broke

lose. The naval escort ships started firing the depth charges and so on for 10 minutes.

Then there was silence. We went back to school and later we heard a loud bang. German

U-boats had been lying in wait at Long Point and sank a corvette. The ship was HMCS

Valleyfield, which was sunk in 1944 with heavy loss of life.”

There was even a spy episode in the area which likely was related to the American

construction of a radar station.

“We using to go fishing for sea trout near where the Anglo Saxon disaster

passengers were buried,” Myrick recalled.

“There was a big old bleached white tree which we used to climb before we went

fishing. One day we noticed a six-foot bough bed by the tree and we thought that was funny

because residents had tilts in the woods if they wanted to stay overnight. We looked at

the bed and we found a little pocket book we couldn’t read.

“We went back to Cape Race and stopped at the radio building. An operator looked

at the pocket book and said it was written in German. A German U-boat likely landed a man

to look at the radar station which was under construction. I don’t think the man lost

the book there. He probably left it to show the Germans knew what was going on.”

In any event, the light was kept lit during the war — there was no blackout at

Cape Race.

There’s also a more tangible reminder of the war off Cape Race. A Hudson bomber

which ran out of fuel lies in 80 feet of water there.

Myrick still has a page from the daily log kept at the lighthouse during April 1912.

The sealing ships Southern Cross and Ranger are noted passing Cape Race. There was

still snow on the ground.

The entry for April 15, 1912 reads:

“The Titanic of the White Star Line struck an iceberg off here last night and went

down. She was on her first voyage and lost 1601 and 746 were saved.”

The SOS distress signal from the Titanic was picked up at Cape Race.

The Cape Race light and fog horn were operated by steam, which meant four large boilers

had to be stoked continually and about 500 tons of coal were used each year.

Before Confederation, the coal, and all other supplies, came by sea from Canada. Even

though Newfoundland was not part of Canada, a small area around the lighthouse was

Canadian territory because of its lease with the British government. And that gave the

residents an unexpected benefit.

“We’d have the Eaton’s catalogue and we used to order from the mainland,”

Myrick said. “Our orders all came in free of Newfoundland taxes and duties. So we

ordered a lot for people from nearby communities and that saved them about 40 per cent on

the cost of the goods.”

He also worked at lighthouse radio stations at Battle Harbour, Cape Bonavista, Gander

international airport aviation radio and at St. John’s marine and air radio stations.

The first lighthouse on Cape Race was built by the British government in 1856. It stood

about 40 feet above the 100-foot cliffs rising from the sea. The light was visible 15

miles at sea.

The current lighthouse was built by the Canadian government in 1907. Ottawa had taken

responsibility to service and maintain the main lighthouses around the Newfoundland

coastline under contract to the British government.

Today, the Cape Race light stands 240 feet above sea level and its light has been seen

50 miles at sea. It remained an important navigational device until the advent of

satellite global positioning.

In its heyday, Cape Race was the point of departure for ships that sailed the great

circle route between North America and Europe.

National

News From Canada.Com International

News From Canada.Com |