Interpreting

Diagrams

Diagrams

generally are of three

types: generalized diagrams, diagrams that represent processes, and

biological

drawings. Generalized diagrams show

biological features (these are not a drawing of any particular specimen

but an

interpretation by an artist/biologist to show the features of something

e.g. a

drawing of an animal cell or a nephron). Diagrams that represent

processes usually

are showing the relationship between several steps in a process e.g. a

diagram

to explain “the triplet code” or the “Loading and unloading of

respiratory

gases” in mammals. Biological drawings are actual drawings of specific

biological specimens showing the precise detail that one can see either

with

the naked eye or microscope. Textbooks usually only have the first two

types

unless they are showing a photograph of something with an accompanying

biological

drawing. The diagrams that you must know for the first year courses are

listed

in the “Course Outline”. Exams may also test your ability to apply your

knowledge

and analyze diagrams that you have never seen before.

Interpreting

Generalized

Diagrams

Generalized

diagrams can be used as a reference for

interpreting actual biological specimens (in the lab) or for

visualizing and

learning content of the course such as the

name, shape, size, features of structures and

their position relative to other structures.

One

of the best ways of learning material like this is to draw your own diagram of the generalized

diagram. The

first time you draw it, draw

and label it while looking at it. Concentrate on the

size, shape,

position and features of the structures so that your drawing is

accurate. Next compare your

diagram to

the original and make sure all details of the

diagram are well represented and labeled correctly. Test

how

much you learned by drawing and labeling it again this

time without looking at it. Again

compare your drawing with the

textbook diagram and make

sure there are no missing elements. If there are errors or omissions

keep on

drawing, labeling and checking it until you are certain that you can

replicate

the drawing on demand.

For

students

in Biology 1002 try this technique on

the

following diagram of a nephron, copied from “Biology 6th

edition” by

Campbell and Reese.

Using Generalized

Diagrams as

References in the Lab

Generalized

diagrams can be used as a means of interpreting what you see with your

naked

eye or with the microscope. Since the size, position, colour,

orientation or

other features of the structures of your specimen may look different

from the

diagram you may have to make some inferences (reasoned conclusions) as

to what

the structures are on your specimen. Some people have no trouble

guessing what

a structure looks like from another view but others struggle with the

concept.

The more practice you get at interpreting specimens from diagrams the

better

you get at it. Suppose you saw structures on your specimen that looked

like

this:

They

may

in fact be structures that are represented on the diagram as:

So

you can

see that sometimes some interpretation is required. Often by looking at

a

number of diagrams of the same structure you get a better idea of

whether you

are correct in your interpretation. In any case this is a valuable

skill to

develop in the lab. The advantage of trying to develop this skill in

the lab is

that there are lots of people that can help you.

A few students completely

misunderstand the

purpose of reference diagrams in the lab. Instead of using reference

diagrams

to interpret specimens and developing those all important interpretive

skills they

simply copy the diagram and go home and memorize the diagram for the

lab exam.

Unfortunately they find out on the lab exam that they won’t be asked to

simply

label a reference diagram that they have studied but they are asked to

draw a

diagram of a specimen and label it. Students that have not developed

the

interpretive skills cannot effectively draw and label their own

diagrams.

Copying and memorizing diagrams does not help with the development of

interpretative skills.

Interpreting

Diagrams that

Represent Processes

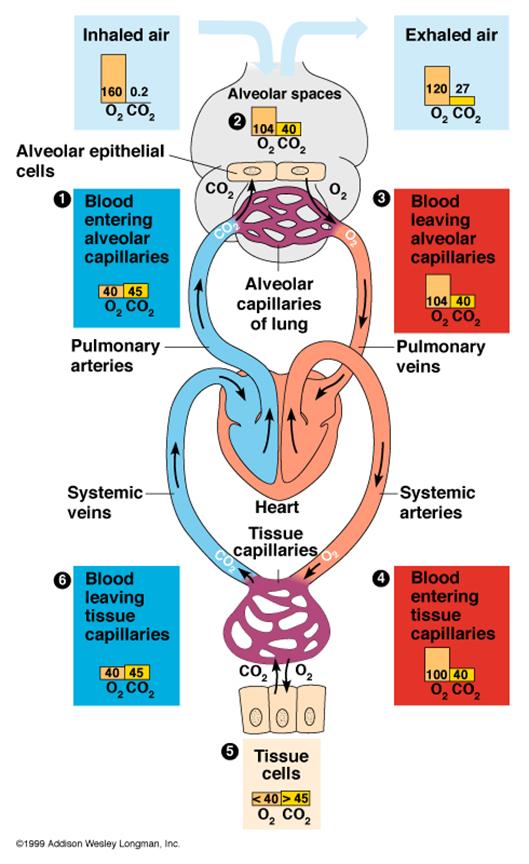

Textbooks

attempt to clarify how processes work by means of diagrams. Mostly

these

diagrams are an attempt to help students visualize the steps of

processes and

see how the steps are related to one another.

In “Biology 6th ed.” the

authors (Campbell and Reese) usually have a detailed word description

of the

steps in a process written under the diagram. In order to understand

the

diagram you first must understand the content that the diagram

represents from

the text. Next you have to relate

the

written description under the diagram to the diagram itself. Sometimes this can

take a long

time to interpret and digest. If you do this stepwise you can draw your own version of the diagram in

understandable

steps and write what is going on in each step on your

diagram.

Sometimes it is hard to see where to

start on the diagram other times it easy. Some diagrams actually number

the

steps on the diagram for you and give you a written description of each

step

(this is particularly true for life cycles: See Fig. 30.17: The life

cycle of

an angiosperm Campbell and Reese (6th Ed.)). In some

diagrams, the

process starts at the top of the diagram and proceeds to the bottom

e.g. Fig.

17.3 Campbell and Reese (6th Ed.) and in others they start

at the

left side and proceed to the right e.g. Fig 9.6 Campbell and Reese (6th

Ed.). Some diagrams do not have a set starting point and/or may lack

the

written description underneath the diagram such as Fig

42.27 Campbell and Reese (6th

Ed.).

After

you

have pieced apart the diagram into steps and written a description of

each step

on your diagram you might try to create

your own written description of the diagram. Make reference to your

own figure and use your own

words. Reread the information under the figure from the book and see if

you

have omitted or misrepresented any content.

Biology 1002

students try

this exercise with Fig 42.27 Loading and unloading of respiratory gases

from

Campbell and Reese (6th Ed.) p 894.

Biology 1002

students may

want to construct their own diagram of a process. Go to Processing

Information/concept Maps/Concept maps 1002/ “Concept Map Exercise 1002

a

process” and try to draw your own word description of homeostatic

control of

water balance by ADH.

--

------