Bell main site page || main goby page --- How it started -- Intro -- Larvae -- recruitment

I have been keen on gobies for a very long time. My work interests me for its own sake, but I always try, whenever there's a choice, to follow (a) what might be useful for conservation, and (b) what others haven't noticed or what seemed too risky.

Goby fry fisheries (based on this group of gobies) are important throughout much of the inter-tropical world, yet because the fish that are harvested are only 20mm or so in length, they have tended to be ignored by fisheries biologists. Yet in the Philippines, as calculated from Manacop's (1953) information, the commercial fishery alone, for northern Luzon alone, was of the order of 20,000 tonnes annually. I remember Vern Pepper remarking that was more than the catch of Atlantic salmon; that was a while ago, so now it's on a par with the catch of northwest Atlantic cod, which was once one of the world's great fisheries. Of course, the goby fisheries have declined also, underscoring the generality of resource abuse.

When I was in high school I thought I would become a conservationist, in the sense of figuring out the things we needed to know in order to conserve. But even before I left high school I realised that we (our governments) were not even making good use of the information we had, so information was not the problem, so becoming a conservationist seemed pointless. But I couldn't get away from biology, even though languages and physics were easier to make sense of, and somehow I became some sort of scientist/conservationist anyway. And, having battled seemingly determinedly bad decisions on Cod for some years, I can understand why people cynically walk away--but the fish can't walk away, so it's up to us not to. As scientists, we have an obligation to nature as well as to our society, and we should never allow ourselves the cynical luxury of giving up before the battle has been joined. Otherwise, our grandchildren will ask us what all those things looked like and tasted like, and we'll be ashamed to tell them what chances we spurned. Well, more on that on other pages, but here let me turn back to what is supposed to be a happy page set.

| I remember the first moment I saw a stream goby in Dominica. I was just out of high school, and I was there with my father, Peter Bell, an artist. He was keen on orchids, I was keen on fish. I had some aquaria, and I had read and re-read W.T. Innes's Exotic Aquarium Fishes, and a few others. (The Innes book is a gem.) I had been disappointed to not go to the Yucatan, but it's difficult to imagine the Yucatan could have held such exciting results. He has since included fish in many of his paintings: That we went to Dominica at all was a fluke -- we had planned to go to the Yucatan but there was some lucky foul-up with the travel arrangements. |

|

We were walking the road that runs

on the east side of Morne Trois Pitons, one of Dominica's two main

volcanoes (quiet but not finished) about 4,000 feet (1200 m) high.

There's

your

first

marker:

this group of fish are worldwide intertropically, but they are

tightly associated with volcanoes. I brought some back to Newfoundland and kept them in aquaria. The

large ones didn't adapt well (and I advise you should never harm

or capture large ones if you can avoid it -- they might be decades

old).

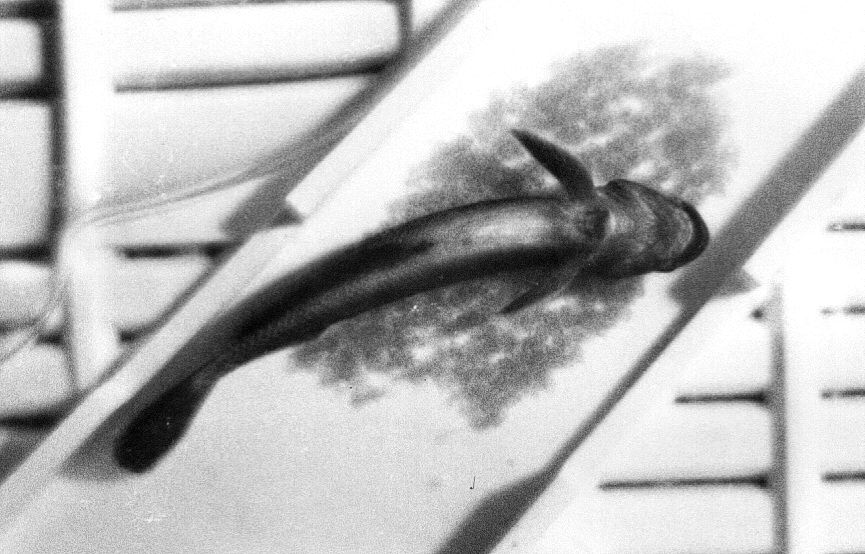

This is the male guarding the nest. |

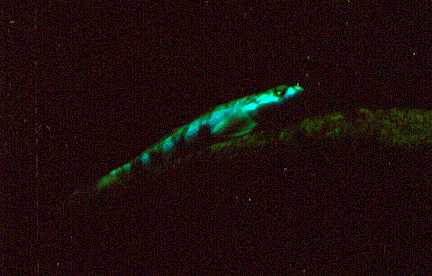

A brilliant blue-phase (territorial colouring) male Sicydium punctatum from Dominica, West Indies, perched on a rock.

Einar Wide, a retired friend in Dominica, and I collecting gobies, while someone from Layou or St. Joseph does her laundry. Multi-use of rivers continues to this day. Some years later I sampled plankton a little way above here, and below. |