After 1895 the Liberal government of Premier Whiteway--who had returned to office in February of that year following the enactment of legislation by Prime Minister D.J. Greene which removed the disabilities imposed on those convicted in the 1894 election trials--was overshadowed by the political and commercial scandals of 1894. Despite having completed the railway in 1897, it would be the cause of his defeat in the 1897 general election to the Tories led by James Winter. Retrenchment policies pursued since 1895 which were unpopular with voters, a severe depression in the fish trade, and the 1895 Confederation talks--all these factors combined to explain Whiteway's electoral defeat. In preparation of the general election, Whiteway's budget earlier in 1897 had attempted to restore the government's unpopularity. These measures included increases to the district road grants and for public works generally, and legislation to construct three new branch lines. The Tory election campaign had emphasized that Whiteway's "Policy of Progress" had failed to provide the much-heralded promise of greater employment and prosperity (Hiller, "A History of Newfoundland, 18741901," pp. 31733).

When Winter assumed office in late 1897, there was little indication for local politicians that the local economy would begin to improve as it did by 1899 as markets for local fish revived. In its first year the government pursued a policy of retrenchment in the civil service (some of which was dictated by partisan motives), revised the tariff to produce increased tax revenues, and floated successfully a $350,000 loan. It also decided to divest the colony of Whiteway's legacy from the "Policy of Progress" by disposing of ownership of the recently completely railway. Under the terms of a railway agreement it signed in 1898 with the Reids, Reid would operate the railway for fifty years (until 1945) in return for additional land grants which would bring his total holdings to about four million acres. At end of that period the railway would become the property of his successors, and for that reversionary interest Reid would pay the colony $1 million. He agreed to operate a coastal steamship and the Gulf of St. Lawrence ferry, providing his own vessels, in return for subsidy payments. Further Reid agreed to take over the government's telegraph lines and to purchase the St. John's dry dock. Other clauses awarded Reid the right to build a street railway in St. John's, and to supply the town with electricity from a power plant at Petty harbour. (Hiller, "The Political Career of Robert Bond," pp. 1617)

The contract Winter made with Reid split the Liberal opposition between Bond and Morris factions. Following the 1897 election, Bond had replaced Whiteway as Liberal leader, apparently having pushed Whiteway (who was personally defeated in his own district) aside from the leadership. A strong nationalist who blamed outside interests for Newfoundland's slow economic development (see Hiller, "The Political Career of Robert Bond," pp. 1314), Bond's damming view of the contract was that it would sell Newfoundland's assets for much less than their market value and create a monopoly in the colony's economy. Morris supported the contract because it would relieve the financial crisis facing the colony and provide much needed employment, particularly in St. John's. Supported by five colleagues he broke ranks with Bond on the issue.

Having being rejected in the Assembly on the railway question, the Liberals circulated petitions throughout the Island calling on the Colonial Office to disallow the legislation embodying the Reid Contract. Altogether, 22,774 signatures were obtained by January, 1899, but the Imperial authorities refused to interfere. In the meantime, it had become known that Receiver General A.B. Morine had acted as Reid's solicitor during the drafting of the Railway Bill and still held that position. Morine had been forced to resign from the Executive Council by Governor Herbert Murray (18951898) but this had split the government party into two camps. The government only survived because of an agreement between Winter and Morine whereby Morine was to become premier and Winter chief justice. Winter, however, did not keep his part of the bargain, because of the opposition of prominent Tories outside the government to Morine's potential leadership. In January, 1899 with the support of 12 government MHAs, Morine attempted to enforce the agreement on Winter. Four leaders-- Winter, Morine, Bond, and Morris--now bargained with each other for political support. Winter was unable to get Bond's backing, while Morine failed in his negotiations with Morris. This brought Winter and Morine back together in preparation for the opening of the legislature in May, the deal now being that Winter would give way at the end of the year. Ultimately, Winter remained in office until March 6, 1900 when he resigned following the defeat of his government on a vote of no confidence. In this vote several of his Assembly supporters had broken ranks to join Morris who in turn threw his support behind Bond's Liberals.

Bond was now asked by Governor Henry McCallum (18981901) to form the government, which he did in alliance with Morris and with a majority of two seats. Later in 1900 Bond faced the electorate with a promise to amend the 1898 Railway Act; he won an overwhelming victory, taking 32 of 36 seats against a Morine-led opposition financed by the Reids. As one St. John's newspaper observed, "one of Mr. Reid's sons has been accompanying him [A.B. Morine] through his constituency, and is mooted as a candidate. Two captains of Reid's bay steamers are running for other seats. The clothier who supplies the uniforms for Reid's officials is another, and a shipmaster, who until recently was ship's husband for the Reid steamers is another" (quoted in S.J. Noel, Politics in Newfoundland, Toronto 1971, p. 30). The account of colonial politics from 1898 to 1900 follows from Hiller, "A History of Newfoundland, 18741901," pp. 35157, 372.

As part of his electoral alliance with Morris, Bond had agreed to amend the railway contract rather than seek its repeal. In July 1901 a new contract was signed whereby Robert Reid gave up his reversionary interest in the railway and control of the public telegraph system and the government returned to him his $1 million with interest. For a payment of $850,000 Reid gave up approximately 1.5 acres in land grants and was permitted to form the Reid Newfoundland Company, which had responsibility for managing Reid's landholdings, and for operating the railway, the coastal steamship services, the St. John's dry dock, and the St. John's streetcar and electrical systems.

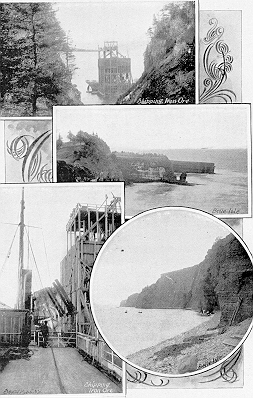

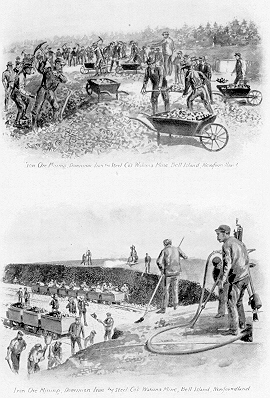

For much of his premiership from 1900 to 1909 Bond presided over a relatively prosperous period (highlighted by a budget surplus of $125,000 for the 190708 fiscal year) and which saw Newfoundland adopt the "Ode to Newfoundland" (written by Governor Sir Cavendish Boyle) in 1903 as its unofficial national anthem. There was considerable new employment, much of which was created by the Reids. By 1911 Reid Newfoundland in the words of journalist Patrick McGrath, the "biggest paymaster on the Island, bigger even than the government itself." In the west end of St. John's the company had constructed a new railway terminus (the first one built in the 1880s was located at Fort William in the city's east end, today the site of Hotel Newfoundland), consisting of railway freight and storage sheds, round houses, general stores, and machine, locomotive, car, and dock shops. The government encouraged the development of coal deposits on the west coast and supported agricultural development. In 1905 it signed a contract with English capitalists to build a large newsprint mill in the Island's interior at Grand Falls on the Exploits River. The development of iron ore mines at Bell Island by Cape Breton steel companies after 1895 also contributed greatly to local revenues.

As the economy was diversifying, labour was also becoming unionized and strikes for higher wages and improved working conditions were more prevalent. Major strikes in the early 1900s involved the iron ore mines on Bell Island in 1900, a sealers strike in St. John's in 1902 and a railway strike at Placentia in 1904 against Reid Newfoundland. Among St. John's labourers leadership was provided by the Longshoremen's Protective Union, formed in 1903 after a strike of dock workers that year. Longshoremen found themselves not only battling their employers to gain wage concessions, but also an influx of labour from the outports in search of employment following the end of the fishing season (source: Jessie Chisholm, "Organizing on the Waterfront: The St. John's Longshoremen's Protective Union (LSPU), 18901914," Labour 26, Fall 1990, pp. 3759, and Robert H. Cuff, "Simeon Kelloway," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. XIII).

During the early 1900s there developed a vibrant native literature to reflect the strong confidence of Newfoundlanders in the future of their country. In his seminal study, The Rock Observed: Studies in the Literature of Newfoundland (Toronto 1979), Patrick O'Flaherty observes that Newfoundland had a "literary intelligentsia, composed principally of St. John's residents with ties to the business and governing elite" (p. 115). While Daniel Prowse's monumental History of Newfoundland had appeared in 1895, St. John's merchant William Gilbert Gosling, for example, published a history of Labrador in 1910 (still the standard work on the subject) and a biography of Sir Humphrey Gilbert the following year. The Newfoundland Quarterly was first issued in July 1901 and it quickly became a booster for local writers and poets. Gosling, Prowse, and others established the Newfoundland Historical Society to preserve and promote the history and culture of Newfoundland. One of the Society's objects was the "collection and preservation of all printed books, manuscripts, records (or copies of such manuscripts and records, properly authenticated) having reference to the history of this Colony and its dependencies, in respect of its tradition, folklore, and local nomenclature; its fauna and flora, and physical geography."

External relations formed a major preoccupation of Bond's premiership. The major issue was Bond's unsuccessful effort to secure reciprocity with the United States, which is discussed extensively in the Hiller and Noel readings in your Book of Readings. Bond's political problems resulting from his poor foreign relations with the American, Canadian, and the British governments prompted his political opponents to rally around the leadership of Edward Morris. In 1904 Bond had easily won re-election when the United Opposition Party won only 6 of 36 seats. This party had five leaders--James Winter, Augustus Goodridge, Donald Morison, William Whiteway, and A.B. Morine--and no real manifesto or policy other than its desire to defeat Bond. The real potential opposition leader to Bond in 1904 lay within his government, Edward Morris who had the sympathetic support of journalist P.T. McGrath and the Evening Herald which advanced Morris's claims on future political leadership (see Melvin Baker, "Patrick Thomas McGrath," Newfoundland Quarterly, vol. LXXXVII, Winter 199293, pp. 3738). In August 1907 Morris made his political move breaking with Bond over a disagreement over wages paid to road labourers in Kilbride in his district. While Morris sat as an independent, P.T. McGrath resigned the editorship of the Evening Herald and founded the Evening Chronicle, ostensibly with funding from Reid Newfoundland. The following year Morris announced the formation of the People's Party which included within its ranks, former tories and an economic interest group tied to Reid Newfoundland and general efforts to industrialize Newfoundland through the attraction of outside foreign capital.

Morris also had the tacit support of Governor Sir William MacGregor, who was unhappy with some of Bond's policies. The first election in 1908 ended in a virtual tie between Bond and Morris. When MacGregor refused to grant Bond another dissolution, Bond resigned the premiership on March 2, 1909. He was succeeded by Morris, who had informed the governor that he could form a government, despite having only the same number of seats as Bond. Not surprisingly, Morris himself sought a dissolution, which was accepted as both sides had now attempted to form a government. In the general election which followed on May 8, 1909, he won handily over Bond.

Source: Melvin Baker, "History 3120 Manual: Newfoundland History, 1815-1972", Division of Continuing Studies, Memorial University, 1994, revision of 1986 edition)