The Island's northeast coast had provided both Whiteway and

Bond with strong electoral support from among the area's fishermen.

Growing disillusionment by fishermen with the political and

economic system enabled a new political movement to emerge in 1908

with the formation of the Fishermen's Protective Union (FPU) led by

William Ford Coaker who in 1910 created a political party with deep

organizational roots in the social life of the outports.

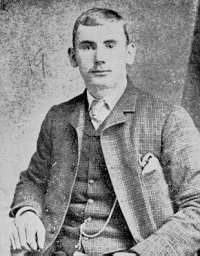

Circumstances were favourable in 1908 for the formation of a fishermen's union, according to Coaker's biographer, historian Ian McDonald. "An unusual large catch coupled with disordered marketing produced a temporary but harsh depression that saw fish prices in many cases cut by half, leaving, thousands of fishermen angry and frustrated," McDonald writes. "However, that depression...was only the occasion for the union's creation, for the underlying tensions upon which it fed had long existed." In 1908 the 37-year-old Coaker was able "to channel the frustrated energies of fishermen and to shape their future course" (McDonald, "Coaker and the Balance of Power" in James Hiller and Peter Neary, eds., Newfoundland in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Toronto, 1980, p. 155).

Born in St. John's the son of a carpenter, Coaker before 1908 had been at various times an outport mercantile clerk for a St. John's merchant, a merchant (who lost everything in the 1894 bank crash), a telegraph operator, a political supporter of Robert Bond in the 1897 election, and a farmer. From the late 1890s he operated a farm on an island near Herring Neck in Notre Dame Bay, where he read widely on the social and political issues of the day.

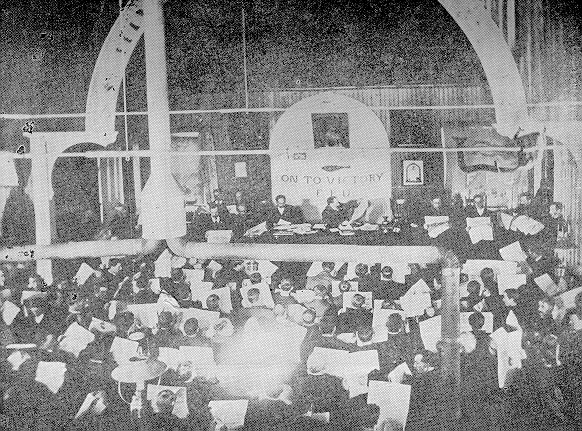

On November 2, 1908 he convened a meeting of fishermen at Herring Neck to found the FPU which adopted as its motto, "To each his own." According to his biographer,

"Coaker argued that the fishermen were exploited by a manifestly unjust economic system, that deprived them of their fair rewards by placing so much arbitrary power in the hands of the merchants. The commercial class along with the government was attacked for its failure to come to grips with the problems of fish quality and international marketing and for failing to improve the working conditions of loggers and sealers." (McDonald, "Coaker and the Balance of Power," pp. 1556)

Coaker was critical of the churches whose clergy failed to provide the leadership to improve the moral tone of public life. Clergymen were more interested in spending education grants on the maintenance of church buildings rather than use for school buildings and the education of illiterate fishermen. The St. John's professional, educational, religious, and commercial classes were parasites living off the productivity of fishermen. In 1910 in the FPU's newspaper, the Fishermen's Advocate, Coaker asked his followers if each received his "own" when

"he boards a coastal or bay steamer, as a

steerage passenger and has to sleep like a

dog, eat like a pig, and be treated like a

serf? Does he receive his own at the seal

fishery where he has to live like a brute,

work like a dog...? Do they receive their own

when they pay taxes to keep up five splendid

colleges at St. John's...while thousands of

fishermen's children are growing up illiterate? Do they receive their own when forced to

supply funds to maintain a hospital at St.

John's while fishermen, their wives and daughters are dying daily in the outports for want

of hospitals?" (McDonald, "Coaker and the

Balance of Power," p. 156)

The FPU proposed a number of proposals that were embodied in the Bonavista Platform of 1912. Among the major ones were the following:

"Such a programme," Coaker told delegates to the FPU's annual

convention in 1912, "should fill every toiler with enthusiasm and

encouragement, for the operation of such a policy would completely

revolutionize the fisheries and be truly a period of progress that

places the toilers' interests above all others for the first time

in the political history of parties in this Colony. Every toiler

should be proud of such a policy and should never rest satisfied

until it is in operation" (quoted in W.F. Coaker, ed., Twenty Years

of the Fishermen's Protective Union of Newfoundland, St. John's,

1984 reprint of 1930 edition, p. 50).

In his efforts to implement the FPU's political agenda, Coaker had to convince either Prime Minister Morris or Liberal leader Robert Bond to adopt such proposals as their own. Coaker did not envision the FPU's political organization, the Union Party, as assuming the reins of political power as rather holding a "balance of power" after the next general election. This political strategy, contained in section 63 of the union's constitution, stated that the Union Party "shall not hold more than sufficient seats to secure the balance of power between the government and the Opposition parties, and no Union member of the Assembly shall be permitted to hold his seat if he sits on the side of the government or opposition..."

The prosperity associated with the first Morris administration

(1909 1913) had been, in part, the result of the coming into

production after 1910 of the Grand Falls pulp and paper mill (for

which the Bond Administration had been responsible for its

establishment) and the resultant increase in the colony's exports.

Local prosperity was also artificially-induced because of Morris'

economically unsound, but politically popular, branch railway line

policy. This policy saw the government spend $7 million for

unnecessary branch lines--more than 50 percent than he had promised--to repay his political debts to the Reid interests, which had

helped him in the 1908 and 1909 elections. By 1914 these expenditures had caused great concern among the Water Street merchants,

who had rallied around Morris in the 1913 election to stop the

political advance of the FPU, but whose support Morris now found

wanting because of his mismanagement of the public finances. To

pay for these expenditures, in the 1914 spring sitting of the

legislature the Morris administration had imposed an increase of

$650,000 in taxes that, therefore, effectively negated the cut in

taxes made prior to the 1913 election. Such policies resulted in

the national debt rising from $23 million in 1909 to $32 million in

1915.

Morris's first administration also enacted legislation in 1911

providing Newfoundland's first old age pension scheme; any male

aged 75 years and older who could prove they required financial

assistance received $50 per year. The implementation of such a

scheme had been discussed since 1907 when the Bond government

appointed a royal commission to investigate old age pensions in

response to a suggestion from A.B. Morine, the leader of the

Opposition. Morine had suggested a pension of $40 annually be paid

to men over the age of 65 years, rising to $50 at age 70 and $60 at

75. Morine's pension proposal would not be needs-tested. The

commission collected the necessary data on various scheme proposals, but the commissioners did not make a report because of the

political confusion surrounding the 19089 period. Both Bond and

Morris made granting old age pensions a feature of their political

platforms in both election campaigns. In 1911 Prime Minister

Morris's government implemented a system that a Canadian expert on

the subject has called the "first state-operated old age pension

scheme in Canada, more than two decades before such a programme was

adopted in any of the Maritime Provinces." Not only was Newfoundland's scheme based on limited funds, but throughout its history to

Confederation with Canada, it was available only to men and

"remained the most blatantly gendered scheme for the needy elderly

in the western world" Successive governments had been able to

control costs by "establishing a fixed limit to the total funds

available for expenditure.

In the first year funds for 400 pensions were voted. These funds were distributed to the various districts in proportion to their total population (rather than to their share of the elderly population or of the poor population). No matter how many elderly men were in poverty, only 400 would receive a pension. Since the elderly were not evenly distributed across the country but the pensions were, inevitably the criteria for acceptance would be harsher in some districts than in others. In some districts long waiting lists occurred, while in others there were vacancies for which there were no applicants. (See James G. Snell, "The Newfoundland Old Age Pension Programme, 19111949," Acadiensis, vol. XXIII, Autumn 1993, pp. 86109)

Having determined that Coaker's party posed no threat to his own electoral re-election chances, Morris rejected overtures of support from the Union Party, which in fact posed a great challenge to Bond's Liberal Party. For the 1913 general election Bond reluctantly agreed to an electoral alliance with Coaker. The Liberal Party was allowed to run five candidates in union areas with the Liberal-Union alliance winning in total 15 seats, 12 of which were in union-dominated districts. Rather than lead the alliance in opposition, Bond instead retired to his farm at Whitbourne leaving the leadership to James Kent, his deputy leader. Coaker was not interested in being leader as he preferred to concentrate on union-related businesses, social, economic, and political reasons which gave rise in the early 20th century to the Fishermen's Protective Union.

On the eve of the outbreak of war in August 1914 in Europe,

the political fortunes of the Morris government had declined

sharply in less than a year since its 1913 re-election. Indeed,

Morris himself was pessimistic of his winning of another election,

which would have to be held by the end of 1917. During the 1914

spring legislative session, the Morris administration found itself

under a barrage of questions from Coaker and his fellow Unionist

members in the Assembly. As Coaker noted in his maiden speech in

the Assembly, it was not "by accident that we have come here. A

revolution...has been fought in Newfoundland. The fisherman,

toiler of Newfoundland has made up his mind that he is going to be

represented on the floors of this House." During the session, the

Unionists questioned daily government policies and programmes and,

on occasion, forced Morris to adopt some legislation he otherwise

would not have. For instance, Coaker got Morris to pass legislation to improve working and living conditions for loggers and

sealers; however, Morris used his majority in the Legislative

Council to strip the legislation of any effectiveness. Concerning

the need for elected road boards in the outports, Coaker got Morris

to agree to a resolution which would see the necessary legislation

enacted at the 1915 session, a promise Morris subsequently kept.

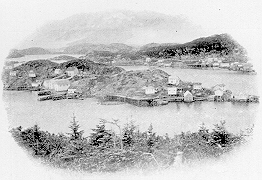

It was against this background of growing public disenchantment with the Morris government that Morris in August 1914 agreed

to a highly unusual procedure for administering Newfoundland's war

effort--the appointment of a committee of citizens. The initiative

for this notion came from Governor Sir Walter Davidson, a

paternalistic and authoritarian representative of the Crown, but

Morris quickly grasped this idea of having such a committee work

under Davidson's guidance. On August 7, 1914, Davidson, with

Morris' approval, had telegraphed the British government that

Newfoundland would raise and equip a regiment of 500 men and

increase the size of the local Royal Naval Reserve from 600 to

1,000 men. Five days later he and Morris organized a meeting of

prominent St. John's citizens which, in turn, unanimously passed

resolutions calling on the Governor to appoint a public committee

to supervise and control Newfoundland's forthcoming part in the

war.

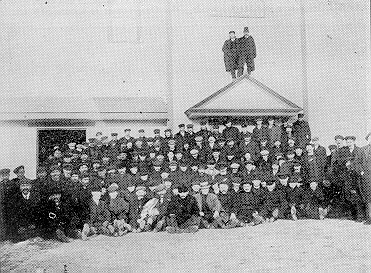

In effect, the Newfoundland Patriotic Association, as it was

named, took on the responsibilities of government that in other

countries were the work of department of militias. For three

years, the Patriotic Association carried out this work without any

legal authorization conferred upon by the legislature. The

Association's central committee eventually consisted of over 250

members, most of whom were St. John's residents. There were also

branches of the Association established in the outports as well,

but throughout its existence the Association was perceived by the

outports as a St. John's organization. The Association had the

following sub-committees to implement its programmes: finance,

reserve force, proclamation, musketry, physical fitness, nominating, equipment, transport, officers, selection, recruiting, non-combatant selection, forestry, employment, food, war history, war

memorial, pay and pensions board, fund raising, and hospital (see

Patricia O'Brien, The Newfoundland Patriotic Association: The

Administration of the War Effort, 19141918, M.A. Thesis, Memorial

University, 1982).

In creating the Patriotic Association, the Morris administration hoped to remove partisan politics from the war effort and,

thus, improve its own public image. To do so, the administration

successfully first got Liberal, and then Unionist support for the

Association. Morris hoped that this broad, political unity would

also divert public attention from the widespread commercial and

economic dislocations and inflation that would certainly follow as

a result of war. It must, furthermore, be noted that the politicians, not only in Newfoundland but also in Europe, believed that

the war would not last beyond the end of 1914. Consequently, the

Morris administration saw the Association as a means of avoiding

the slow, cumbersome, and expensive process of establishing the

necessary government machinery for directing Newfoundland's war

effort.

Finally, since Morris was unwilling to enter into a coalition

government with the opposition and thus put his administration

under the direct influence of the Union Party, the Patriotic

Association for Morris was a way around the problem of creating a

unified political front. The Liberals proved receptive to this

non-partisan approach and three important Liberals--leader J.M.

Kent, J.A. Clift, and W.F. Lloyd, editor of the Evening Telegram--

joined the Association's central committee. As for Coaker, he

initially opposed the Association's formation and demanded an

immediate emergency session of the legislature to deal with

economic problems in the fisheries. Specifically, he believed that

Newfoundland's military contribution should be made through an

expansion of the existing Royal Naval Reserve, for which the

Imperial government would pay much of the cost. A land force he

considered to be extravagant and wasteful and one that could only

lead to increased taxation. Coaker also wanted fish price supports

and public regulation of prices for provisions to control the cost

of living, demands which Morris could not seriously consider

because of Water Street opposition. By the time in September 1914

Morris did call the legislature together, the existence of the

Patriotic Association was well-established and Coaker eventually

supported the Association.

Despite the existence of the Patriotic Association, public

support for the Morris administration continued its downward slide.

In early 1916 Morris sought to weaken the Liberal-Unionist

opposition through the appointment of Liberal leader J.M. Kent as

a judge of the Supreme Court. However, this tactic backfired as it

drove Lloyd, the new Liberal leader, and Coaker into a more formal

alliance on March 25 in anticipation of a forthcoming election

scheduled to be held within the next year, an election they

confidently believed they would easily win. In December 1916

Morris secretly got permission from the British government to

extend the life of the legislature by one year if necessary.

On May 25, 1917 Morris approached Lloyd and Coaker to form a coalition government out of the three political parties under his continued leadership. While the Liberal-Unionist alliance was preparing for the election due sometime in 1917, Morris took no measures to improve his own party's chances for the election. The only action he did take was to appoint in May 1917 a High Cost of Living Commission to investigate profiteering allegations against Water Street merchants, many of whom played prominent roles in the Patriotic Association.

The opposition, buoyed by public anger over the profiteering

charges, rejected Morris' overtures for a coalition. The June 8

publication of the Commission's first report only tended to

reinforce the confidence of the Opposition. That Report revealed,

for instance, that a flour combine operated in St. John's and that

at least $600,000 in excess profits had been made by importers.

The Report also exposed that one large shipping company had

increased its rates by an estimated 500 percent. The Commissioners

observed that they could find no justification for such large rate

increases. Public disenchantment in St. John's became manifested

in a successful month-long labour strike in 1918 following the

formation of the Newfoundland Industrial Workers' Association

(NIWA) among the employees of Reid Newfoundland for higher wages.

(Further details on the strike is examined in a recent article by

Peter McInnis, "All Solid Along the Line: The Reid Newfoundland

Strike of 1918," Labour 26, Fall 1990, pp. 6184.)

On June 15 Morris publicly announced his intention to have

legislation enacted extending the life of the House of Assembly by

one year. Faced with the reality of a postponed election, Lloyd

and Coaker struck a secret deal with Morris for the creation of a

coalition government, a deal of which Morris did not tell even his

closest supporters of some its provisions. The essence of this

deal was that the Liberals and Unionists would join with the

majority people's party members to form a coalition cabinet

composed of equal representation from all three groups. There was

also a guarantee of an election in 1918. Morris would continue to

be Prime Minister. The secret part of the deal provided for

Morris's resignation as Prime Minister by the end of 1917 and his

replacement by Lloyd. Morris also agreed to opposition demands for

the establishment of a militia department to assume the work of the

Patriotic Association and for the imposition of a tax on business

profits. Thus, on July 17, 1917, the National government took

office with Morris as Prime Minister and Lloyd and Coaker as

influential cabinet ministers. Soon afterwards, Morris left

Newfoundland to attend the Imperial War Conference leaving Lloyd as

acting Prime Minister and, in effect, in control of government.

One of the first acts of the National government was the

passage of an extension bill, extending the life of the Assembly

for another year. Other legislation provided for the creation of

the promised militia department, the imposition of a profits tax

act which imposed a tax of 20 percent on net business profits for

the calendar year 1917 in excess of $3,000, and the restriction of

the powers of the Legislative Council in money matters. Coaker was

also able to provide a guaranteed price for fish to fishermen by

setting a price and warning that the government would not issue

insurance policies to exporters offering to buy fish below the set

price. At this time, there was a shortage of local tonnage--the

Water Street merchants had sold many of their ships to Russia,

under the guise of helping the war effort, for lucrative

profits--and merchants had great difficulty in securing private

insurance policies for sailing vessels carrying cod to the

Mediterranean markets. The National government also created a

shipping department under the direction of John Crosbie to handle

tonnage matters.

As the end of 1917 neared, rumours circulated of Morris'

pending resignation (Morris was still in England), but his people's

party supporters dismissed them as idle speculation. Yet, the

resignation did occur in late December 1917, with Morris accepting

an appointment to the British House of Lords as Baron Morris of

Waterford. However, Morris never got the appointment of Newfoundland High Commissioner to Britain, which apparently was part of the

deal in setting up the coalition cabinet. When his former people's

party supporters remaining in cabinet found out about this pending

appointment, they vetoed the nomination out of anger in being duped

by Morris, who had negotiated such a profitable exit for himself

out of Newfoundland politics.

The Lloyd National government, which took office on January 5,

1918, had to face the difficult problem of deciding whether to

implement conscription to provide needed manpower for the depleted

Royal Newfoundland Regiment. This was a problem which Morris had

managed to avoid in the past, but on April 9, 1918, the British

government informed Newfoundland that the Regiment would have to be

withdrawn, if more recruits were not forthcoming. The Regiment was

short its authorized establishment by 170 men and that it needed

300 men immediately and 60 per month thereafter. By April 1918

Newfoundland already had had over 8,000 men in all the services,

while it rejected another 6,246 volunteers on medical grounds. The

overall casualty rate for the Regiment was 20 percent, a figure

more than double that for the Canadian army. The most famous

battle the Regiment took part--and one that had the most disastrous

effect-- was at Beaumont Hamel on July 1, 1916, when the Regiment

suffered an appalling casualty rate of 90 percent.

The Newfoundland government also found itself under pressure

locally from various groups for conscription as well. In early

1918, for instance, the Loyal Orange Order, the Society of United

Fishermen, and the Methodist Church Conference--all St. John's

based--passed resolutions in support of conscription. The

Presbyterians expressed similar support, while the Roman Catholic

Church remained quiet on the issue, its silence being akin to

consent. Within St. John's itself, there was general support both

for the war and conscription. The outports, however, were a

different matter and the people strongly opposed conscription

because of the nature of outport economy and society. For outport

fishermen, conscription meant a disruption in the fishery, since it

would take badly-needed manpower from a fishery which was now

experiencing considerable war-induced prosperity. The loss of men

not only affected families but also whole communities, especially

those communities dependent on the Labrador schooner for their

economic survival. In the spring of 1918, then, the booming

fishing economy was already short of manpower, and parents were

reluctant to allow their sons to become volunteer recruits, let

alone conscripts. Fish prices between 1915 and 1919 were 65%

higher than their 191014 average (Hiller, "Newfoundland Confronts

Canada," p. 447).

Coaker was well aware of the strong outport aversion to

conscription, but he faced strong pressure within cabinet to

support conscription. His choice was to either support Lloyd or to

withdraw the support of the Union Party from the National government. On April 13, 1918 Lloyd announced that his government would

first hold a referendum on the conscription issue, a posi-tion

Coaker reluctantly supported in public. However, the Newfoundland

government bowed to British pressure and announced that conscription would be brought in without a referendum, a move it decided to

take since it feared a referendum vote would go against conscription. On April 26 Coaker announced that he supported this new

position by the National government, despite the many anti-conscriptionist messages that had flowed into FPU headquarters for

the past month. The membership reaction to his decision was quick

and swift. FPU Councils met and passed resolutions condemning

Coaker's position, in which his members perceived him as favouring

St. John's interests over those of the outports. In some Union

homes pictures of Coaker were smashed, while in Union Council halls

the instruments of authority were either returned to headquarters

or turned against the wall. Coaker had decided to support

conscription, because the National government had proven itself

receptive to Union--sponsored measures since its formation in July

1917 and his continued presence in such a government he considered

necessary to implement a FPU fishery reform programme. To soften

the blow of conscription and legislation extending the life of the

Assembly for another year, the Lloyd government also passed an

income tax to cover those professional and middle class people

whose incomes were not taxed by the 1917 business profits tax.

It was Coaker's hope that the mere passage of the conscription

act itself would stimulate increased voluntary enlistment by the

May 24 deadline for the registration of conscript eligible men.

This is exactly what happened. Six hundred men enlisted by May 24,

thereby providing the Regiment with sufficient numbers to meet its

needs until the end of September. While a campaign by war veterans

no doubt had the desired effect in securing more volunteers, others

enlisted voluntarily rather than wait to be conscripted. In the

end, those who registered for service did not have to report for

duty until September 1, 1918, because of the availability of a

sufficient number of volunteers. Instead, they received a leave of

absence without pay until October 15, by which date they received

a further leave of absence until November 15 because of a local

epidemic of influenza. With the end of war on November 11, the men

were given an indefinite leave of absence. While none of the men

ever saw active duty, the implementation of conscription did have

serious political repercussions on the FPU and divisions developed

among the members, some of whom would never hold Coaker in the same

esteem as they previously had.

While Coaker found the National government much to his liking

and even some people's party politicians found they could work in

harmony with Coaker, the opposition of Archbishop Edward Roche and

the Roman Catholic Church to the FPU had remained unchanged.

Although he had failed in his bid to prevent the creation of the

Lloyd government, in May 1919 Roche was successful in having the

government defeated in the Assembly. It was Roche's goal that the

old alliance of Roman Catholics and the Liberal Party be forged

once more under the leadership of the retired Sir Robert Bond.

Thus, to retain Roche's support for his own future leadership

ambitions and future support in Roman Catholic districts as well to

win the support of the Water Street merchants, Michael Cashin, the

leader of the people's party, decided to make a break with the

government. In doing so, it was Cashin's hope that Roche's

enthusiasm for Bond would soon subside and that Bond would not

return to active politics.

On May 20, 1919, Cashin rose in the House of Assembly and

moved a vote of non-confidence in his own government. When nobody

else stood to second the motion, Prime Minister Lloyd rose and did

so, much to the surprise and laughter of other members in the

Assembly. Lloyd did so presumably because he believed that Cashin

did not really intend to bring down the government; rather, it

apparently was Cashin's intent to have the motion not carry and

Lloyd continue on as Prime Minister depending on his political

survival on the people's party wing of the coalition and thus

separate Lloyd from the Union wing. Cashin had counted, it seems,

on the motion failing through some of the people's party members

either abstaining or even voting against the non-confidence vote.

Once the motion failed, Cashin then would be able to disassociate

himself from the Lloyd government, while at the same time being

able to defeat the government through the withdrawal later of

support by the people's party. Thus, Cashin hoped to ingratiate

himself with the Water Street merchants for having split with

Coaker and, hopefully, impress Roche with his forthright stand in

trying to defeat the Coaker-influenced National government.

Lloyd's action, in any case, foiled whatever strategy Cashin

had had in mind, for the Assembly unanimously passed the motion.

Governor Sir Alexander Harris then called on Cashin to form a new

administration, which included former Liberal Albert Hickman and

former Unionist John Stone. As for the remaining members of the

Union Party, they remained a strong, united force under Coaker's

leadership, while the Liberals were in disarray following Lloyd's

acceptance from Prime Minister Cashin of a position as registrar of

the Supreme Court. Leaderless, the Liberals spent the summer of

1919 awaiting a decision from Bond to their request that he return

to lead them in the forthcoming general election. Hovering in the

background to seize the mantle of Liberal leadership, if Bond

remained retired, was a former Morris protege who in January 1918

had broken with the Lloyd national government, Richard Squires.

Elected as a MHA for Trinity in 1909, Squires had lost his

seat in 1913 and accepted an appointment to the Legislative Council

and served as Morris' Colonial Secretary. Following his break with

Lloyd, Squires had established his own newspaper in preparation for

his leadership ambitions. Despite being a Morris supporter, local

party affiliations were fluid enough for Squires to switch easily

to Liberal ranks without his action creating a political backlash.

Once Bond declared his intention to remain retired, "I have had a

surfeit of Newfoundland politics lately, and I turn from the dirty

business with contempt and loathing," Bond wrote to a Liberal

power-broker who quickly threw his support behind Squires--Squires

immediately set his plans in action. On August 21 he launched a

new political party, the Liberal Reform Party, and entered into

negotiations with Coaker for an electoral alliance, agreement

finally being consummated on September 22.

The alliance was a marriage of convenience between the two

leaders who mistrusted each other. Yet, each man needed each other

to achieve their goals--Squires to attain the Prime Ministership and

Coaker to achieve political power to implement the various

fisheries reforms long sought by the FPU. Under the agreement

between the two, the FPU would be allowed to run candidates in

three districts previously reserved for Liberals, thus giving the

Unionists the ability to win 12 seats in the Assembly and form the

largest single block of influence in any Squires-Coaker administration (a small group of seats would be controlled by William Warren,

a Bond Liberal). Squires also agreed to allow Coaker a free hand

as the Minister of Fisheries and Marine to shape fisheries policy

as he wished. In the November 3, 1919 general election, the

Squires-Coaker alliance won 24 of the 36 seats in the Assembly,

thus placing Coaker in a strong position of power to address the

pressing problems which he felt threatened the Newfoundland

fisheries.

Source: Melvin Baker, "History 3120 Manual: Newfoundland History,

1815-1972 (St. John's, Division of Continuing Studies, Memorial University

of Newfoundland, 1994)