Two of the earliest and least known efforts in St. John's to

provide public housing for the town's working poor took place in

1919 and 1920. The first housing development was undertaken by

the Municipal Council which constructed 22 houses between 1919

and 1920; the second was a government supported initiative from

the business community in response to the municipality's foray

into the housing field and resulted in 1920 in the building of 30

houses. Both projects represented the culminative result of a

decade of public concern and debate by residents as to how the

town's poor housing condition could be improved through a

possible program of slum clearance and suburban development.

In particular, those tenements located in the central residential heart of St. John's that had been hastily put up following the town's major fire of July 8, 1892, were of great concern from both fire protection and public health standpoints. This area was bounded on the north by Harvey Road, on the south by Theatre Hill and New Gower Street, on the east by Carter's Hill, and on the west by Springdale Street. The neighbourhood was the most densely populated section of St. John's and its most unsanitary. (1) A government health inquiry in 1910 noted that in this area "a very large number of tenements are totally unfit for human habitation. They are so bad that they cannot but degrade those who live in them physically, mentally, and morally." The inquiry warned that these dwellings "are from year to year getting steadily worse. They grow more rotten, more leaky, more unsanitary, and more infected with Consumption and other germ diseases". (2) Indeed, in this neighbourhood sewerage connection was uncommon, and Council's sanitary carts a nightly presence. Throughout the whole town, in 1914 there were approximately 4,500 to 5,000 residents living in 900 to 1,000 tenements who were dependent upon the service offered by these carts. As might be expected, there was a concomitant health problem. In 1912, out of a total population of approximately 34,000, the town's death rate was 18.5 % per one thousand births; for Newfoundland as a whole, the rate was 16.79 per thousand. According to calculations made in 1914 by a St. John's civic reform committee, the death rate in the town was higher than in Glasgow or London. Infant mortality was another problem of continuing severity in the capital. Out of 866 deaths in 1912, 23.1 % had resulted from diseases of infancy and childhood. Most of these were directly attributable to unsanitary conditions; those who lived in cellar tenements and enjoyed little fresh air were particularly exposed. What the merchants and the wealthier citizens wanted was to shift the labouring poor to tenements in the growing suburbs. For their part, despite the appalling conditions, the labourers living in the heart of the town wished, in the absence of an adequate system of public transporatation, to remain close to their places of work along the harbour front. (3)

Public concern in St. John's in the early l900s over the state of

housing reflected in part a growing awareness by residents of the

problems of municipal government and population growth, which was

an aspect of the broader wave of municipal reform that had been

sweeping Canadian and American cities since the 1890s. (4) In St.

John's the spirit of reform was probably first manifested in the

field of health, and centered on a vigorous public campaign waged

to rid Newfoundland of tuberculosis - or consumption as it was

commonly called - one of the most prevalent fatal diseases in the

colony. As a result of the efforts of the Newfoundland

Association for the Prevention of Consumption which was formed in

1908, the People's Party government of Edward Morris (1909-1917)

in the following year appointed a royal commission to look into

the state of health conditions in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Among those nominated to the Public Health Commission were the

Honourable John Harvey and William Gilbert Gosling (two members

of the fish exporting firm of Harvey & Company), and St. John's

Mayor Michael Gibbs, a lawyer and member of the Legislative

Council who was a minister in the Morris administration. (5) In

their report to the government in 1910, the Commissioners

stressed the urgency of providing better housing for the poor if

health standards were to be raised both in St. John's and in

Newfoundland in general. (6)

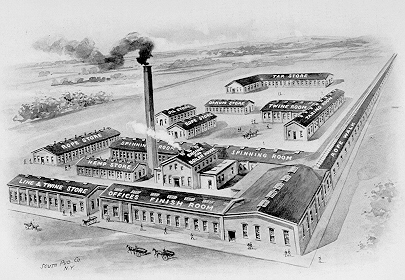

In 1911, St.John's politicians met to discuss how a better standard of housing could be obtained for their town. On September 18, the six St. John's representatives in the House of Assembly (which included Prime Minister Morris), and the Municipal Council under Mayor William Ellis unanimously agreed that the best approach would be to ask the major employers of labour to erect dwellings that would be available to their workers at a reasonable annual rental. Already there were precedents, Morris optimistically noted at the September 18 housing conference, for this course of action. For example, the Colonial Cordage Company, which had been opened in 1882, had constructed houses for its employees just outside the town's limits and near the location of the factory.

Other examples, he continued, were to be found in the company houses erected at Bell Island after 1895 by the new iron mining company there, and at Grand Falls alter 1909 by the paper company in that community. Although the St. John's businessmen were sympathetic to this housing appeal, no definite action was taken by them to follow through with such a building plan, the cost being considered prohibitive. (7) One firm, Harvey & Company, gave the matter close consideration, but eventually decided against the idea. The firm could not devise a housing scheme for its labourers that would return at least 2 1/2% or 3 1/2% annual interest on its capital investment while at the same time providing for the creation of a sinking fund to repay the principal. (8)

There was little that Council could do to develop public housing

under its existing legal authority as contained in the town's

1888 Local Government Act and its subsequent legislative

amendments. What power Council did have in the housing field by

1911 dealt for the most part with water and sewer connections in

houses from street mains, but even in this area it had no

stringent regulations to control new building and the opening of

new streets. Part of the problem was that Council officials had

never strongly enforced the regulations; consequently, a building

permit was often granted by Council without its officials first

ensuring that the proposed building lot was connected to a street

main. In any case, while plans of new buildings or alterations

were required to be approved by Council, Council apparently

neither kept these plans on file nor carried out any systematic

inspections of the buildings to ensure that the plans would be

adhered to. (9)

To see St. John's "grow in a well-ordered and suitable manner"

was one of the aims of a civic reform movement launched in

December, 1913, by the town's Board of Trade and its civic-minded

president, William Gilbert Gosling who for the past few years,

had been studying civic government in St.John's and elsewhere.

Formed on December 29 with Gosling as its chairman, the goal of

the Citizens' Committee was to make a thorough study of the

town's problems and to recommend possible solutions to the House

of Assembly during its 1914 session. (10) One subject which

received close examination was, expectedly, housing. Having

ascertained that a labourer could afford to pay a maximum of

$39.00 per annum on rental accommodation, the Committee's Report,

made public in February of 1914, devised a housing scheme it

hoped would meet the financial needs of the working poor.

Assuming that a building loan would have to be borrowed at an

annual interest rate of 4 %, the committee envisaged a housing

project consisting of three-storey concrete tenement houses with

four tenements on each storey. Each tenement itself would consist

of a living room, water closet, and from one to three bedrooms.

The construction of such a tenement house was estimated at

approximatley $8,000. If the rental of each tenement was

calculated at 75 cents per week, investors would receive an

annual return of 2 l/2 % on their financial involvement in the

housing scheme; if the rental was based on a weekly rate of one

dollar, then the annual return would be 4%, thus leaving

sufficient funds to form a sinking fund to pay off the original

loan. Whether or not the Council should guarantee the interest on

this loan was a matter raised but left unanswered by the

Committee". (11)

The result of the Citizens' Committee's work was the appointment

by the Governor-in-Council of a twelve-man Municipal commission

to replace the elected Municipal Council and to administer the

town's affairs for one year. Out of twelve Commissioners, nine,

including Gosling, had served on the Committee. Eleven of the

twelve Commissioners had commercial or industrial backgrounds;

the twelfth - Jim McGrath - was the president of the

Longshoremen's Protective Union (LSPU). Several of the

Commissioners had previous municipal experience and included,

from the outgoing Council, Mayor Ellis and Councillor James

Mullaly. Two members from previous Councils were called on to

serve on the Commission (or Municipal Board as it was also named)

- Legislative Councillors John Anderson and John Harris. Upon

assuming office on July 2, 1914, this Municipal Commission under

Gosling's chairmanship proposed to draft a new municipal act that

would be based on the members' experience in governing St.

John's. This draft bill would first be submitted to the people in

a plebiscite; if the popular verdict were favourable, it would be

presented to the legislature during the 1915 session. (l2)

Having spent their first five months in office dealing with the

town's services, the Municipal Commissioners on December 1, 1914

turned their attention to the procedure for the drafting of a new

municipal bill. This matter, it was now agreed, would be

discussed at a series of special Tuesday evening meetings. (13)

Considerable progress was made at these meetings but a draft

bill, or Charter, as it came to be called, was still not ready

when the legislature convened in April, 1915. Nevertheless, the

Commissioners presented the Morris Administration with a general

outline of the principles they believed the proposed Charter

should embody. On the housing front, the Commissioners agreed in

principle that Council should have authority to build, let or

sell houses or to make loans to building societies for such

purposes. Moreover, the government would be asked to appoint an

advisory commission to assist Council in the establishment of

town planning, building and housing regulations. (l4)

Subsequently, Prime Minister Morris secured legislation to extend

the life of the Municipal Commission until June 30, 1916, with a

new Municipal Council to be elected to take office the following

day. (15)

When the completed Charter was presented to government on March

28, 1916, it showed that Gosling and his fellow Commissioners had

provided for a possible strong role by Council in the housing

field. In a letter sent ten days earlier to president Jim McGrath

of the LSPU, Gosling outlined what he had in mind. Council would

assist building societies wishing to build houses for working men

by guaranteeing loans to be raised for that purpose. In instances

where an individual wished to build his own house, if it did not

exceed $800 in value to construct, Council would give that person

a bonus equal to 10% of the cost of construction. Moreover,

Council itself would be empowered to buy land and lease it or

sell it as building lots, or to build houses, and to lease or

sell them. If Council were to become directly involved in

building houses, it would do so on land it owned that first would

be laid out and connected to water and sewer mains in the streets

to be opened. Once this was done, Council would construct

semi-detached frame houses on the building lots. A prospective

buyer would be required to make an initial payment in cash of

one-quarter the cost of the house and pay the remainder over a 20

or 30 year period. (l6)

Because of the great amount of detail involved in the Charter,

Prime Minister Morris decided to refer it to a Joint Select

Committee of the legislature. The Assembly's representatives

included the St. John's MHAs, while John Harvey and Michael Gibbs

were among those chosen from the Legislative Council. (l7) Morris

also decided to convene a public meeting to give citizens an

opportunity to examine the Charter before it received legislative

approval. Out of this April 6, 1916 meeting, which was attended

by more than 1500 people, came a Citizens' Committee of 30

members to examine the Charter and report on it to the Select

Committee of the legislature. Those appointed to the Committee

included representatives of the town's wholesale and retail

merchant community, professions, and unions. Unlike the Citizens'

Committee which Gosling had organized in late 1913, the 1916

committee did not include any of the major Water Street

merchants, who continued to work through Gosling, one of their

own. (18) At its first meeting, held on April 12, the new

Committee decided to ask the legislature to postpone action on

the Charter until 1917 to give it more time to study the proposed

legislation thoroughly. (19) The Committee's approach was shared

by the Joint Select Committee, which subsequently received

permission from the legislature to sit out of session and report

back on the Charter in 1917. (20) Consequently, legislation was

passed at the 1916 session providing for members of the Municipal

Council (to be elected in June, 1916) to hold office for two

years. This new Council was to have the same composition as the

one before the 1914 constitutional change: a mayor and six

councillors elected at large on a household franchise. (21)

Gosling was a candidate for mayor in the 1916 campaign while six of his fellow Commissioners ran on one ticket for Council. These were Charles Ayre, F. W. Bradshaw, and Francis MacNamara, all merchants; Jim McGrath; Isaac Morris, a sailmaker; and J. W. Withers, the King's Printer. Gosling and his Commission associates appealed to voters to maintain continuity in municipal government by emphasizing their resolution to have the Charter passed by the legislature. This was necessary, Gosling noted, for the Charter was vital to any further course of action Council could pursue to provide housing for the poor. (22) Gosling's rival for mayor was Walter A. O'D. Kelly, a vice-president of the new Citizens' Committee and a dealer in building supplies. (23) The focus of Kelly's attack on Gosling and the Commission was his criticism of the reorganization of the sanitary system and the institution of the hopper service, which saw catch-basins placed throughout the town for the use of residents who did not have water closets. The waste water deposited in these basins ran off through the connecting street drainage system, while the night-soil was either strained into the sewers by municipal employees or collected by the sanitary carts, whose number was reduced with the introduction of the new system. Kelly claimed this system was "contrary to all rules of health and civilization." He did not offer any specific remedy, but attempted to link the outbreak of communicable diseases in the town to existing sanitary practices. (24) With this approach Kelly polled 1,780 votes on election day, June 29, compared with Gosling's 2,244. Gosling's total was the largest ever polled by a mayoralty candidate, (25) but his margin of victory was not nearly as impressive, and, of his fellow Commissioners, only Ayre and Morris were elected. The failure of the "Commission" ticket owed much to the popularity of the individual candidates involved as well as to the strong rumour that the return of the Board members would lead to a great increase in taxation. (26)

On July 10, 1917 the Joint Select Committee reported that because

of the demands which had been made on its members by the war

effort, it had not been able to devise a bill based on the

Charter and the changes proposed to it by the Citizens'

Committee. (27) In the circumstances, the Select Committee

suggested a further postponement of consideration of the Charter,

noting that three of the St. John's seats in the Assembly had

become vacant because of death and resignation. Not surprisingly,

the decision of the legislature was to extend the life of its

Select Committee and to empower it once more to sit out of

session. (28)

Disappointed by these developments, Mayor Gosling asked the

Morris Administration in July, 1917 to pass certain sections of

the Charter on which the council, the Citizens' Committee, and

the Joint Select Committee were in agreement. (29) Under the 1917

Municipal Act, Council was empowered to use its funds towards the

building of houses for the working poor. This assistance was to

be offered through the letting and selling of houses or by

lending or guaranteeing funds to building societies seeking to

help those in need. Such societies were to be given a bonus of

10% on the cost of any house built for the designated group, the

value of the house not being greater than $1,000. The new limit

of $1,000 rather than the previous $800 had been included in the

Act at the suggestion of the Citizens' Committee. The bonus also

applied to an individual who built his own house. (30)

Gosling's efforts in the next few years to secure government

support in providing financial assistance to Council's housing

plans were complicated by a great crisis in colonial politics.

Re-elected in 1913, the Morris Administration was required by law

to hold a general election by the autumn of 1917. During the 1917

session, however, because of the war effort an Extension Act had

been passed prolonging the life of the existing Assembly by one

year. The price Morris paid for this Act was the establishment of

an all-party National Government to include representatives of

his People's Party, the Liberal Party, and the Union Party, which

had great strength among the fishermen in the northeastern area

of the island and had first elected members to the House in 1913.

Under this arrangement, Morris resigned the prime ministership in

December, 1917, retiring to England where he was elevated to the

House of Lords. (31) His successor was Liberal leader William

Lloyd, whose National Government postponed any action on the

Charter during the 1918 session, claiming that it was not yet

ready to move on the matter. The new government did, however,

pass legislation extending the life of the Municipal Council

first from June 30, 1918, to December 31, 1919, and later to June

30, 1920. The Charter was not enacted by the government until

1921. (32)

Despite the changes of government in colonial politics, by 1919

Mayor Gosling had been able to make some headway in his efforts

to construct houses for the working poor and returning war

veterans. Council's ability to act on the authority it had been

given in the housing field by the 1917 Municipal Act was

initially greatly impaired because it was not given land

expropriation powers. When this omission was corrected in 1918 by

a new Act (the one that also extended the life of Council to

December 31, 1919), Gosling moved quickly to acquire the

necessary land and in July,1918, purchased title to land in the

East End of St.John's as a building site. (33) This land,

situated on Quidi Vidi Road south of the General Hospital, had

been bought from the government in 1907 by Michael Connors, a

farmer, on condition that it would revert back to the Crown at

any time it was needed for improving the town. (34) Also in July

Council asked the government for a $25,000 loan in support of its

building plans. (35) Council's plan was to use this money to lay

out the land, provide water and sewerage pipes for the streets to

be opened, and over a period of time construct houses which would

sell for approximately $2,000 each. Prospective owners of these

houses were to be required to make a down payment of $500 and to

pay off the amount owing over a ten-year period. House and land

were to be held on a 99-year basis, with the lessee paying

Council a perpetual ground rent of $20 per annum; lessees, could,

however, purchase the land freehold at any time during the life

of the lease by giving Council a sum equal to 20 years rent on

the property. The revenue which Council collected from the

selling and renting of these houses would be used to form a

sinking fund to pay off the original construction loan. (36)

The Lloyd Government refused to fund this scheme, as well as a

second plan the Council proposed in November, 1918, asking for an

additional $25,000 to offset increased building costs. The

Government's view was shaped in part by its concern that the

housing project might cost Council more than it could afford.

Some members of the Executive Council, moreover, opposed the

scheme on the grounds that the provision of housing should not be

made a matter of public concern. Gosling responded on November

23, 1918, by telling Colonial Secretary William Halfyard that the

principle of municipal housing was no longer a "matter which the

Executive Council is called upon to consider." The only question

that should concern the government, Gosling wrote with an air of

exasperation, was whether Council could afford to pay the

interest on the loan it was requesting. (37) In the end Council's

view won out; on June 4, 1919, the Executive Council guaranteed

the principal and interest on a $50,000 loan to be secured from

the Royal Bank. (38) By December, 1919, Council had constructed

twelve six-room semi-detached frame houses. (39)

The following year Council completed and sold another ten houses

in the same area, but this initial building effort ended

Council's direct involvement in the public housing field. The 22

houses turned out to be more expensive than Council had

originally anticipated because of high labour and material costs;

in fact, the high cost prevented Council from selling them to the

working poor for whom the houses initially had been intended.

(40) In any case, in June, 1921, for business and health reasons

Gosling retired from civic office and St. John's subsequently

lost its strongest supporter of municipal intervention in the

housing field. (41) Moreover, by the time of Gosling's retirement

the momentum for providing housing for the poor had swung greatly

in the direction of private enterprise.

Indeed, while Council had been active with its building program,

its efforts were quickly being overshadowed by a more ambitious

scheme put forward by the town's businessmen who had secured the

support of government, church, and labour in their endeavour. The

main supporters of this venture were John Anderson, Michael

Gibbs, and Jim McGrath. In March, 1919, Anderson presented their

proposal to a meeting of the Newfoundland Industrial Workers'

Association, a general labour union formed at St.John's in 1917.

They proposed a joint stock building society that would build 600

houses on the outskirts of St. John's for both members of the

working poor and returning war veterans. Houses in the slum area

would then be torn down and a better class erected. Anderson was

subsequently successful in forming the Dominion Co-operative

Building Association, which set out to raise a capital stock of

$2,000,000. A resident of his proposed housing estate would own

both his house and the land on which it stood, in return for an

annual rental payment to the Association of an amount of not more

than 10 per cent of the total cost of construction, estimated at

about $1,500. Association houses would be cheaper than the

Council's, Anderson claimed, because union members would give

some free service in the construction phase. (42)

When the Association received its act of incorporation in 1920,

it was also given some generous financial concessions by the

Liberal Government of Richard Squires, which had come to power in

November, 1919. Squires gave the Association a 20-year guarantee

on the annual shareholders' payment of dividends on its capital

stock if annual payments were less than 5 per cent of paid up

capital. He also consented to allow the Association to import

duty-free all building materials which could not be obtained in

Newfoundland. In return for these concessions, the Association

shareholders agreed to allow the government to appoint one-third

of the Association's directors. (43)

The site for Anderson's proposed houses was a tract of land in

the northern outskirts of St. John's on Merrymeeting Road, which

was owned by the Roman Catholic Church. Archbishop Edward Patrick

Roche gave this land to the Association at a nominal rent for

disposal by the association on either a freehold or leasehold

basis to prospective house buyers. Roche stipulated that the land

was to be used only for house construction. (44) Its early

optimism notwithstanding, by mid-1920 the Association was unable

to raise the capital to begin construction and in July asked the

Squires Administration to guarantee the principal and interest on

a $25,000 loan it hoped to obtain from the Royal Bank. In spite

of this guarantee, no substantial funds were forthcoming from the

business community and on September 17 the Squires Administration

agreed to guarantee a further $25,000 which the Association

secured from the Royal Bank. (45) With these loans in hand, the

Association pressed forward, opening 30 houses for sale on

December 1, 1920. (46)

This burst of building enthusiasm ended the Association's housing

scheme, the 30 houses falling far short of the hoped-for 600. As

was the case with the Council's experience, the Association found

that high labour and material costs had driven up the price of

their houses from the expected $ 1,500 to $3,000 each, an amount

the working poor could not afford. (47) Moreover, from its

beginnings the Association had financial difficulties that would

eventually result in the company's being placed in liquidation.

The association's directors apparently kept no strict accounting

system to record how the Association spent the money it received.

Consequently, the Association failed to repay the Royal Bank the

$50,000 it had borrowed to construct the houses in addition to

the interest on this loan which, at the end of 1924, stood at

nearly $9,000. Because the government had guaranteed this loan,

on November 17,1924 Attorney-General William Higgins took action

in the Supreme Court to have the assets of the Association

liquidated. (48)

While businessmen saw no future financial advantage in

constructing houses for the working poor, after 1921 the

Municipal Council also shied away from such a course of action

for reasons of economy and principle. Not only was the city

unable to afford further ventures in public housing, but

successive councils were against the notion of public housing.

Thus, it was not until 1944 that the city again became actively

involved in the housing field. On this occasion, Council joined

with the Commission of Government to fund the St. John's Housing

Corporation which the latter had set up in July, 1944. The

purpose of this public body was to undertake the building outside

city limits of a large suburban development which was eventually

incorporated as part of St. John's and locally known as Churchill

Square. Completed in the 1950s, this new suburb was not the

answer, however, to the city's continuing slum problem. Indeed,

the houses constructed by the Corporation were designed for use

by the city's returning war veterans and middle class and were

too expensive for the working poor. Since the city could still

not afford its own slum clearance scheme, any concerted effort

after 1944 to rid St. John's of its slums had to await

Newfoundland's entry in 1949 into the Canadian Confederation and

the subsequent infusion in the 1950s and 1960s of Federal funds.

This new funding resulted in the demolition of most of the

central slum areas and the resettlement of its residents to

public housing projects jointly sponsored by the Federal and

Newfoundland Governments in the city's suburbs (49) With regard

to the city's own role since 1949 in providing houses for the

working poor, it was not until 1981 that Council again took up

the mantle of leadership in public housing that Gosling had first

shown in 1919; in that year, the city decided to re-enter the

public housing field through the construction of its own houses.

1. Trade Review Commercial Annual, March 26, 1910.

2. Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador, PANL, GN2/5, Special File of the Colonial Secretary's Office, file 119-A, Colonial Secretary Robert Watson to Prime Minister Edward Morris, January 22, 1910.

3. Melvin Baker, "William Gilbert Gosling and the Establishment of Commission Government in St. John's, Newfoundland," Urban History Review, vol. IX, no. 3 (February 1981) 42-3.

4. Gilbert A. Stelter and Alan F.J. Artibise, eds., The Canadian City: Essays in Urban History (Toronto 1977) 337-418.

5. Edgar House, Light at Last: Triumph over Tuberculosis in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1900-1975 (St. John's 1981) 10-7.

6. PANL, GN2/5, file 119-A, Watson to Morris, January 22, 1910.

7. Daily News,September 19, 1911; and PANL, P8/B/11, Board of Tade Papers, Special File, "Report of the Executive Committee of the Citizens' Committee, February 12, 1914," 6-9.

8. Daily News, April 30, 1913.

9. "Report of the Executive Committee of the Citizens' Committee, February 12, 1914," 6-9.

10. Baker, "William Gilbert Gosling," 47.

11. "Report of the Executive Committee of the Citizens' Committee, February 12, 1914," 6-9.

12. Baker, "William Gilbert Gosling," 47.

13. St. John's Municipal Council (St. J. M.C.) Minute, December 1, 1914 (located at City Hall, St. John's).

14. A.N. Gosling, William Gilbert Gosling: A Tribute (New York, n.d.) 64-7; and Journal of the House of Assembly, JHA, 1915, Appendix, 496-504.

15. Satutues of Newfoundland, 6 George V, Cap. 6.

16. St. John's M.C. Letter Book, William Gosling to Jim McGrath, March 18, 1916.

17. Proceedings of the Newfoundland House of Assembly, PNHA, 1916, 354.

18. Daily News, April 7, 1916. See also PANL, PB/A/23, Warwick Smith Papers, "Minute Book, Citizens' Committee on Municipal Bill, 1916."

19. PANL, PB/A/23, "Minute Book, Citizens' Committee on Municipal

Bill, 1916."

20. PNHA, 1916, 506, 556-59, 580-81.

21. Statutes of Newfoundland, 6 George V, cap. 3.

22. Daily News, June 23, 26, 28, 29, 1916; and Evening Telegram, June 10, 17, 19, 1916.

23. Daily News, April 13, June 20, 1916.

24. Evening Telegram, June 26, 27, 28, 1916.

25. Daily News, July 3, 1916.

26. Ibid., June 29, July 6, 13, 1916; and Evening Telegram, June 28, 1916.

27. PNHA, 1917, 441.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid., 450. See also St. J.M.C. Minutes, May 31, June 21, July 5, 1917.

30. PNHA, 1917, 157; and Statutes of Newfoundland, 8 George V, Cap. 12.

31. S. J. R. Noel, Politics in Newfoundland (Toronto, 1971), 123-25.

32. Melvin Baker, "The Government of St.John's, Newfoundland, 1800-1921" (Ph.D. thesis, The University of Western Ontario, 1980), 366-79.

33. St. J. M. C. Minutes, May 23, July 11, 1918; and Statutes of Newfoundland, 8-9 George V, Cap. 3.

34. PANL, GN2/5, file 27-J, J. L. Slattery to Colonial Secretary Richard Squires, November 20,1917.

35. Ibid., Slattery to Colonial Secretary Halfyard, July 19,1918, and William Gosling to Halfyard, November 23, 1918.

36. Proceedings of the Newfoundland Legislative Council, PNLC, 1920, 178-82.

37. PANL, GN 2/5, file 27-J, William Gosling to Colonial Secretary Halfyard, November 23, 1918.

38. PANL, GN9/1, Minute of Executive Council, June 4, 1919.

39. Daily News, May 15, 1920; and Gosling, William Gilbert Gosling, 86-7.

40. Evening Telegram, November 9, 1926.

41. Gosling, William Gilbert Gosling, 108- 12.

42. Daily News, March 29, June 24, July 12, 1919.

43. PNLC, 1920, 172-89, 194-206; and PANL, GN9/1, Minute of Executive Council, June 11, 1920.

44. PNLC, 1920, 175.

45. PANL, GN9/1, Minute of Executive Council, July 16, 1920; and Newfoundland Supreme Court Registry, "Petition of Attorney General William J. Higgins, November 17, 1924."

46. "Homes for the Houseless," The Newfoundland Magazine (November, 1920), 7-8; and Daily News, August 11, December 3, 1920.

47. Evening Telegram, December 8, 1925.

48. Newfoundland Supreme Court Registry, "Petition of Attorney General William J. Higgins, November 17, 1924"; and In Liquidation #485 file "Domminion Cooperative Building Association (located in the Newfoundland Registry of Deeds and Companies, Confederation Building, St. John's).

49. Melvin Baker, "In Search of the 'New Jerusalem': Town

Planning and Public Housing Policies in St.John's, Newfoundland,

1917-1944" (paper presented to the Canadian Historical

Association, Ottawa, June, 1982).43